She remembers the date: Aug. 22, 2013.

That’s the day MU journalism student Megan Armstrong, then a sophomore, attempted to take her life. It was a Thursday, and her roommate wasn’t home. She felt excited as she prepared to carry out the task.

But then something stopped her. Armstrong says her vision went cloudy. She remembered how much death scared her. She saw the faces of the people she loves and the things she still wanted to do. “I had an anxiety attack during my suicide attempt,” she says, laughing at the irony.

Waking up the next day was hard because she had to face what she almost did. She hadn’t planned to tell anyone, but her cousin, who also deals with mental illness, must have realized something was off when they talked that day. He called her parents and told them they needed to get to her — now.

After driving to Columbia, Armstrong’s parents found her on a bench near Cold Stone Creamery on Elm Street. She looked dazed. She doesn’t remember much of that day. What she does remember is going home with her parents and having to tell them what she did — what she had almost done.

Being with her friends and family was the most traumatizing part for Armstrong. “When you’re in that place in your mind, that stuff crowds up everything you actually care about,” she says. “But then they’re right in front of you, and you can’t ignore them.”

She counts herself lucky, she says, because her family helped her find the support she needed. Armstrong has regularly been to therapy since she was a sophomore in high school. When she went to college, she continued to talk to a therapist in Kansas City over the phone, but following her suicide attempt, she and her family found a therapist in Columbia she is comfortable with. Today, she quotes what her therapist says in conversation, making jokes about their close relationship. She’s doing better now. She’s on track to graduate.

A Growing Crisis

Armstrong is one of more than 5 million college students struggling with mental health, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the country’s largest grassroots mental health organization. Rates of anxiety and depression, in particular, have skyrocketed in what many are calling a crisis of mental health on college campuses.

Like Armstrong, more students than ever come to college on medication or in treatment for mental health problems, according to a report by The Chronicle of Higher Education in 2015. More than 25 percent of college students have a diagnosable mental illness and have been treated in the past year, according to NAMI.

At MU, 61 percent of 1,010 college students who responded to an American College Health Association assessment in fall 2014 reported feeling overwhelming anxiety within the last year. And 35.5 percent said they “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function.”

Mental health problems don’t just start in college. According to Psychology Today, “the average high school kid today has the same level of anxiety as the average psychiatric patient in the early 1950s.”

In an October 2014 article in The Atlantic, high school nurses describe daily encounters with students suffering from anxiety. Amber Lutz, a counselor at Kirkwood High School in St. Louis, says students are experiencing high-performance expectations as the competition rises for sports, school and future universities. Students show up to the nurse not for skinned knees or a spare tampon, but for panic attacks.

Dr. Sharon Sevier, former chair of the board of the American School Counselor Association and a counselor at Lafayette High School in St. Louis, says increased levels of testing also contribute to the stress and pressure of the students she sees.

In a blog for Psychology Today in 2010, developmental psychologist Peter Gray says the public school system has turned away from a philosophy of teaching for competence and now teaches students that it is more important to get good grades than be allowed to truly explore what interests them. It’s a system, he says, that “is almost designed to produce anxiety and depression.”

More students than ever come to college on medication or in treatment for mental health problems, according to a report from The Chronicle of Higher Education.

The millennial generation, which includes ages 18 to 34, has a reputation of being whiny, self-important and coddled, constantly patted on the head and rewarded by parents and teachers for the smallest triumphs. They were raised to be competitive, to achieve, to collect accomplishments and awards the way other generations might have collected GI Joes or pet rocks. Many members of this generation have come to see themselves as above average. They work hard, and many believe they deserve rewards for their effort.

But for all of their preparation, millennials could be the first generation to make less money than their parents, according to the latest numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau. When they enter college, millennials, raised to be successful fish in high school ponds, find themselves competing with more fish for what will eventually be even fewer jobs. What’s worse, they are more aware of their peer’s social and professional achievements than ever before, thanks to the filtered highlight reels of Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat.

There are many reasons college students might experience anxiety and depression. As more students from varied backgrounds, classes and ethnicities attend college at higher rates, the challenges they face can be new, unexpected and isolating, according to Christy Hutton, assistant director for outreach and prevention at the MU Counseling Center. At the same time, students who are expected to go to college by either their family or society feel pressure to be more successful than perhaps ever before.

The effects of these pressures are becoming more drastic. Suicide is the second leading killer of college students — a rate that has tripled since 1950, according to the ACHA. Dan Jones, past president of the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors, has noted an increase in self-harm behavior, including suicide ideation or cutting. Professionals say the young people they see have trouble expressing feelings and dealing with discomfort or negative emotions. “Millennials don’t feel comfortable struggling,” Jones says. “They don’t have the resilience of previous generations.” He attributes this to a lack of problem-solving skills due to parents continually removing all obstacles for their children.

College age millennials were taught they were unique compared to others. And in the case of mental health, it seems to ring true.

Duck Syndrome

Heather Parrie, an MU junior sociology major who just ran for Missouri Students Association vice president, holds several student leadership positions on campus. She looks like the quintessential co-ed: ombré blond hair, thin frame, a no-nonsense baseball hat paired with an oversized T-shirt, a phone that dings with emails and a planner filled with meetings. She’s the type of college student whose accomplishments parents brag about to their friends on Facebook and in holiday cards.

In spring, Parrie was hit with something unexpected. Burdened with the weight of the expectations and relentlessly comparing herself to successful friends, she began to crumble. In the grips of self-doubt, anxiety and depression, she began sleeping up to 20 hours a day. She canceled plans with friends, skipped class and preferred to stay wrapped in a safe cocoon of blankets in her sorority house. She ended up failing an accounting test and then the class itself, which just made things worse. In April, she was diagnosed with anxiety and depression.

Even in her darkest moments when she felt she’d never get out of bed, Parrie managed to conceal her inner battle from most people.

When she later asked friends if they noticed her struggling, they told her, “You always look like you have it together, so we didn’t ask you if you needed help.”

Researchers and mental health professionals explain the gap between college students’ tireless efforts to appear put together and their inward unraveling as the “duck syndrome.” The term was first coined at Stanford University for the common conception that anxiety and failure are seen as unacceptable at the school, and it was closely mirrored by the term “Penn Face” at the University of Pennsylvania, where students have striven to appear happy even when they aren’t.

The idea is this: Picture a duck swimming across a lake or pond. On the surface, the duck seems to be gliding along effortlessly, gracefully. But beneath the surface, the duck’s webbed feet are busy paddling — frantic, fraught, desperate — to keep itself afloat.

Parrie’s battle with this façade has been played out in headlines about college students who took their lives or contemplated doing so. A recent New York Timesarticle chronicled the struggle of Kathryn DeWitt, a student at Penn who attempted to take her life after facing extreme pressures at college. In May, ESPN’s Bleacher Report published a piece about another Penn student, Madison Holleran, a gifted runner who took her life freshman year. According to the article, Madison carefully crafted her social media accounts to show a happy, fulfilled life. But she struggled to connect her outward projection to herself, “as though she could never find validation for her struggle because how could someone so beautiful, so seemingly put together, be unhappy?”

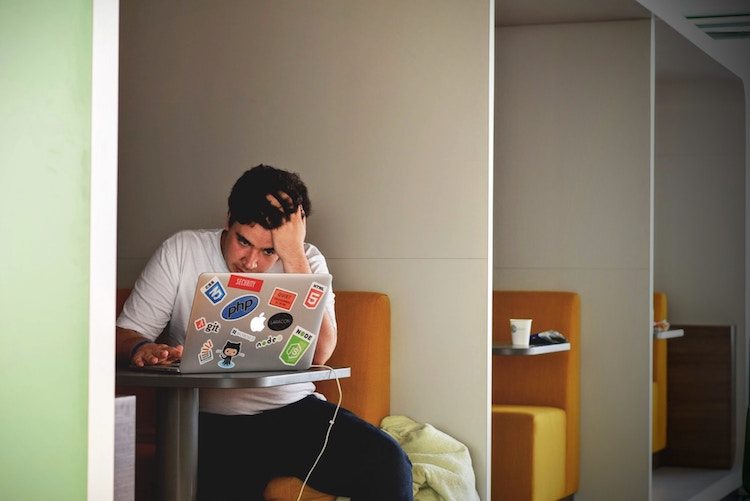

In a fall 2014 assessment, the American College Health Association found that the top three factors that were affecting students’ academic performance at MU were stress, anxiety and sleep difficulties. (Photo: Tim Gouw)

In July, after battling her mental illness for many months, Parrie wrote a blog post. She wrote about her journey with mental illness and described her reasons for getting a tattoo of a semicolon. In literary terms, the punctuation mark is used to take a pause, but another phrase always follows it. For Parrie, this was a symbol for her continued fight against mental illness.

The post went viral and reached an estimated 7 million people and even helped inspire a new trend in tattoos. It was shared or written about on Huffington Post, the International Business Times and Buzzfeed, to name a few. In the post, she delves into the duality of her carefully crafted outward appearance of success versus her inward battle against her perceived failure.

She writes: “I am depression, and I am the perfect picture of a 20-year-old sorority girl at an SEC school. I am depression and I am oversized fraternity formal T-shirts and Nike shorts that hang off my frail, starved hips that the Greek Town girls envy so much. I am depression.”

Achievement Pressure

There are certain commonalities in the stories of college students such as Parrie who struggle with depression and anxiety, but one in particular illustrates the intense pressure they feel to achieve, and it often comes from parents.

“My parents expected me to be very successful,” Parrie says. “They weren’t overbearing, but they expected me to be my best.” For Parrie, her best meant working toward a 4.0 high school GPA, being in the top 5 percent of her class, nailing the ACT and filling her résumé with extracurriculars.

That kind of drive doesn’t stop once students get to college. “Students are juggling a lot of roles,” Hutton says. Many students have a hard time balancing their laundry list of responsibilities, including taking 12 to 15 credit hours, working part-time jobs or internships, engaging in clubs and student leadership, maintaining relationships and dealing with family obligations, Hutton adds. It’s overwhelming, and students struggle to keep up.

“I was always taught that if you work hard, you’re going to be OK,” Parrie says. Millennials, though, are finding this isn’t always the case. Many parents and teachers have given their children and students resources, means and motivation to succeed, so they are expected to constantly achieve. Students often build debt, work at unpaid internships and make physical and mental sacrifices to stay competitive, all to enter an ever-growing pool of applicants whom internships and employers sift through. In a 2012 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 44 percent of recent grads aged 22 to 27 with at least a bachelor’s degree were underemployed, which means they were working in jobs that didn’t require a college degree.

A happiness study started in the 1970s by Jean Twenge, author of Generation Meand professor at San Diego State University, found an unusual trend: People aren’t becoming happier as they get older. According to a 2015 Associated Press article about the study, young adults could be suffering from “economic insecurity,” which means they fear they won’t be able to achieve all they expected. “Our generation is the pioneer for not seeing the light at the end of the tunnel,” Parrie says.

“I was always taught that if you work hard, you’re going to be OK.”

—Heather Parrie, MU student

Millennials strive to succeed, but they haven’t always been taught to deal with the times when they inevitably fail. As Jones puts it, they haven’t been allowed to struggle before. Because of the way this generation was raised, Jones says, “people don’t get used to the idea that they’re not always number one or not always the best.” This leads to college students feeling self-doubt at substantial levels.

This generation oftentimes deals with “helicopter parents.” These parents choose college classes for their children, call universities to ask about a bad test score and even tag along to job interviews. A more recent term for a similar parenting style is “lawn mower parenting,” in which parents mow down the obstacles in their children’s way. A 2011 study by Terri LeMoyne and Tom Buchanan at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga found that students with helicopter parents are more likely to be medicated for anxiety and/or depression.

Indiana University psychologist Chris Meno says in an article by the Indiana University News Room that college students are psychologically affected by this style of over-parenting because they have not yet figured out the balance between independent decision making and asking for help.

Twenge headed another study that examined the results of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory — a mental health survey given to college students since 1938 and high school students since 1951. She noticed that many students have shifted focus from intrinsic to extrinsic goals. In other words, students have gradually begun valuing material awards and outside approval over self-improvement or fulfillment. In the 1960s and 1970s, most college freshmen valued “developing a meaningful philosophy of life” over “being well off financially.” Today, that exact opposite is true.

Many college students’ self worth is based on their achievements, whether that fulfills them or not. Parrie is no different. “I pride myself on being a strong, hardworking, mentally sound person,” she says.

Armstrong shares the same craving for achievements. “My therapist says I have a tendency to want to accomplish really special things all the time.” Armstrong says when she does something she’s proud of — like when she published a novel, Night Owls, in May to reflect her mental health struggles or organized fundraising events in Chicago — the warm, bright feeling of accomplishment wears off faster each time and leaves her empty and searching for it again.

The College Debate

Demand increases for mental health services at universities

Throughout the past several decades, universities have been given more responsibility for their students’ well-being. As parents and media became more concerned with the safety of campuses, the legal and social pressures put on universities have resulted in a more comprehensive view of the responsibilities universities have toward their students.

But with the demand for mental health services increasing, universities began to enter what former president of the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors Dan Jones calls a perfect storm of setbacks. Universities were seeing their federal or state funding reduced, which meant mental health services weren’t given as much money. Because of the recession, many of the private practice services at universities closed down. And on top of that, Jones says, “many centers were dismantled by politicians in the name of reform.”

Despite limited funds, resources and outside support, university mental health centers are seeing more clients than ever. Jones says a campus mental health center can expect to service 10 percent of the student population at least once. In 2007, MU’s enrollment broke a record for the fifth-straight year at 28,070.

In the 2015 school year, MU again welcomed the largest enrollment on campus with 35,050 students. That means, using the conservative 10 percent rule, the counseling services will attempt to service almost 700 more clients this year than in 2007.

Other factors are contributing to counseling centers across the country becoming overwhelmed. Jones says that more students are seeking help — not only because there are more students, but also because more of them are experiencing problems such as anxiety and depression. There is also less of a stigma for them to seek help. And with the growing panic on campus shootings and the mental illness factor that might play into that, university mental health centers have been expected to set up procedures, education and treatment options for troubled or troubling students.

Social Media

A riddle: What do you get when you pair a generation of people who were raised to be competitive and success-driven with a seemingly smaller world connected through social media?

The answer: A lot of anxiety and overwhelming feelings of inferiority.

Millennials are the first generation to go through all the trials of reaching adulthood through the ever-present lens of social media. According to a 2013 study by the Pew Research Center, social media usage for people between the ages of 18 and 29 increased 1,000 percent in the past eight years. Up to 98 percent of college students use social media, according to Experian Simmons, a consumer insight service.

Experts and those who work with college students are still questioning if all that screen time has changed the way students interact with people face to face. Craig Rooney, director of behavioral health services at the MU Student Health Center, says he’s seen more social anxiety in students. “I’ve wondered if social media and phones have contributed to that,” he says.

Armstrong describes the difference between her parents’ college experience and her own. “My mom, for instance, she didn’t know anything else that existed outside of Baker University — even outside of her tennis teammates and her friends in her sorority. And it was the same with my dad.”

Now, she says she is constantly made aware of her peers’ activities through social media. “You’re constantly hearing about what this person did that was really awesome. It always makes me wonder, what am I doing? What should I be doing? Is it enough?”

Rajita Sinha, director of the Yale Stress Center, told Business Insider that social media often contributes to college students’ stress when it is used to perpetuate harassment or bullying (or, at MU, anonymous Yik Yak threats during the height of a campus protest). But, Sinha says, social media also exaggerates anxiety because students use it to compare themselves with their peers.

An often-sited MU study this year connected heavy Facebook use to feelings of envy, which led to increased symptoms of depression. In a thesis last year by Angie Zuo at University of Michigan, she found that college students who spend time on Facebook engage more in social comparison with their peers. And the more college students compare themselves, the more they showed signs of low self-esteem and mental health problems. Millennials are spending an average of 3 hours and 12 minutes engaging with social networks every day, according to data curated by The Wall Street Journal in 2013.

In a study this year, researchers at MU found that users who experience envy on Facebook can then experience symptoms of depression. (Photo: Mikayla Mallek)

Many times, the feelings inspired by seeing a friend’s Facebook or Snapchat create what researchers and marketers call “fear of missing out” or FOMO. To this generation, even a night out can become a bragging point, or another way to prove they are living a seemingly exciting life.

Essena O’Neill, a 19-year-old Instagram star from Australia with half a million followers, quit social media in late October, saying farewell in a teary final YouTube video. She quit because, as she said in an Instagram post: “Social media … isn’t real. It’s a system based on social approval, likes, validation in views, success in followers. It’s perfectly orchestrated self-absorbed judgment. I was consumed by it.”

After her announcement, O’Neill went back and recaptioned several of her Instagram photos to describe the behind-the-scenes process. In one photo, she is lounging on a beach towel doing homework. She wrote: “Stomach sucked in, strategic pose, pushed up boobs. I just want younger girls to know this isn’t candid life, or cool or inspiration. It’s contrived perfection made to get attention.”

Researchers often refer to social media as a person’s “highlight reel,” where people post the shiniest parts of their lives while never addressing the humdrum daily activities or failures.

College students who understand that social media is used as a near-constant high school reunion, among other things, put extreme care in creating a positive online presence. Even now, after Parrie has received treatment and is better able to deal with her mental illness, she says social media makes her more critical of herself. “They’re showing their best life, and you’re seeing the ugliest part of you,” she says.

Awareness and Acceptance

Millennials have grown up under increased attention on mental health disorders: ADD, depression, eating disorders and suicide are some of the most talked about. They watch it play out — mischaracterized or not — on news reports, in books and TV shows, in their friends and in themselves.

Parrie says watching some of her friends go through depression from an early age is what made her realize she needed help. “It didn’t take me very long to get help in comparison with most people,” she says. “I think that’s because I’ve had so many friends from high school who dealt with it. I was able to recognize in myself what I’d seen in my friends.”

Millennials as a generation have benefited from the gradual slack for the stigma of mental health. Despite being harder on themselves, millennials were found to be more accepting of others with mental illness than previous generations, according to a survey conducted by American University this year. Of those surveyed, 85 percent said they would have no problem making friends or working with someone experiencing a mental illness. Millennials are more accepting and supportive of others and more open to those who lead different lifestyles, the study says. They cheer one another on across various platforms, support LGBT rights, believe racial diversity increases the quality of a campus or workplace and have a more diverse group of friends than previous generations.

LGBT Mental Health

LGBT students are much more likely to experience discrimination.

This community often struggles to find a sense of belonging on a college campus, which can exacerbate or trigger mental health disorders.

At MU, staff at the Behavioral Health Center and the Counseling Center are trained to support these students. Craig Rooney, director of the Behavioral Health Center, is openly gay, which he says can be important for some students to know as they seek help.

The following data was collected by The Healthy Minds from a 2013 survey of 14,000 college students.

By the Numbers:

23.5%

thought about committing suicide in the past year

18.4%

have had bad experiences with medication or therapy, compared to 6.7 percent for heterosexuals

11.7%

said the services offered aren’t sensitive to people struggling with sexual identity

But when it comes to themselves, millennials still carefully craft how others perceive them: Fewer than 50 percent of respondents said they would be able to talk to friends and family about seeking help.

At MU, the local Active Minds chapter, a nonprofit group dedicated to mental health awareness and education, is working to make it easier to get help. Anthony Orso, vice president of the organization, says the ultimate goal is to reduce the stigma enough to create a “supportive community that encourages people to seek treatment.”

“Our students, they’re coping in a lot of ways, but they’re coping.”

—Danica Wolf, MU RSVP Center coordinator

In a big step toward acceptance of mental illnesses on MU’s campus, Active Minds successfully petitioned the administration to put the MU Counseling Center’s number on the back of student ID cards. That’s vital, Orso says, because it shows that mental health is just as important as other forms of personal safety, such as MU Police Department and STRIPES, a student-run safe-ride program.

Many MU administrators are working with students and student groups to increase awareness and education for mental health. Wellness Resource Center director Kim Dude says that during some presentations, students are asked to raise their hands if they have witnessed a friend drink too much. She says pretty much all raise their hand. Almost as many raise their hands when asked if they are concerned about a depressed friend.

“We have a student body who does care,” Dude says. “So it’s about teaching them how to care and teaching them the warning signs.” The bystander intervention training — often associated with a sexual assault intervention program called Green Dot through the Relationship and Sexual Violence Prevention Center — is one of the first lines of defense. Dude says they train more than 1,000 people a year for the program. One of the things they learn to recognize are signs of a person struggling with mental illness and how to help that person or direct them to get help. With signs of suicide ideation, she says, there are specific steps. But in other cases, they’re teaching “just how to be a good human to other humans.”

Millennials might have trouble with resilience, but as Danica Wolf, coordinator of the RSVP Center, says, they’ve made it this far. “Our students, they’re coping in a lot of ways, but they’re coping.”

Multicultural Resources

Students who are ethnic minorities often experience several different compounding layers of stress

In a 2013 study of minority students at the University of Texas at Austin by The Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, African-American students were more likely to feel stress directly related to discrimination. Asian-American students often reported experiencing “imposter feelings” when people didn’t believe they deserved the success they’ve achieved.

The researchers behind the study believe stereotypes that are often and strongly applied to minorities play out in the students’ perceptions of themselves — and that can include how much success they expect of themselves.

One of the problems of serving minority students, though, is that there is not as much research compared to white students. Part of the issue is that minority populations, especially black communities, hold a stronger stigma against mental health and seeking treatment, according to a study this year by The Ohio State University.

At MU, staff at the Counseling Center and Behavioral Health Center report that African-American students are seeking help at a slightly higher rate.

Staff has been reaching out to the community with more presentations and outreach about mental health. It has connected with groups such as the Legion of Black Collegians, the Black Culture Center and other minority groups. Often, the students come to the staff and ask for them for assistance with the programming.

The Behavioral Health Center and the Counseling Center have non-white therapists who work with students, including a therapist fluent in Mandarin and Cantonese. In its second year, a People of Color support group through the Counseling Center allows minority students to discuss problems such as encountered racism, micro-aggressions and living on a majority-white campus.

In lieu of recent protests on campus, students are looking to increase this outreach and programming at MU. In a list of demands, Concerned Student 1950 says, “We demand the University of Missouri increases funding and resources for the University of Missouri Counseling Center for the purpose of hiring additional mental health professionals; particularly those of color…”

University Involvement

As part of students’ primary care, the Student Health Center screens all of its patients for behavioral health issues, including depression, anxiety and substance abuse. (Photo: Davide Cantelli)

In a back room of the Wellness Resource Center on the MU campus sits a massage chair that students can rent out for 15 minutes. Dude says 1,200 people used it last year just to sit and have moments to themselves.

Terry Wilson, co-project director of health promotion and wellness at the Student Health Center and coordinator of the Contemplative Practice Center, says student demand led to the growth of several mindfulness-based classes. MU’s Contemplative Practice Center won the Best Practices in College Health award by the American College Health Association in 2015. The center offers sessions in mindfullness yoga and meditation, stress reduction and biofeedback. Several of the courses can be taken for credit.

Wilson says the Loving-Kindness course in particular has blown her away with the change she sees in students. She says students who had previously been dependent on alcohol or drugs tell her “they decided that’s not what they want to do anymore.” Wilson says students learn “how to work with difficult people in their lives, or really just how to love themselves.” It’s something Wilson believes is important to this generation of students on campus, especially with the boiling-over tension of recent weeks.

Millennials still carefully craft how others perceive them: Fewer than 50 percent of respondents said they would be able to talk to friends and family about seeking help.

One focus of her classes is to make students feel comfortable with their stress and struggles. “They think they’re flawed and broken,” she says. “We’re all part of the human being club.”

Wolf says she’s seen an increase in the interaction between student groups working together to help one another feel heard and understood. She says faculty and student groups are working to give students the chance to share their stories with one another. “We all crave connection and community,” she says. “There’s so much power in hearing, ‘Me, too.’”

Moving Forward

For students such as Armstrong and Parrie, seeing hope from a place of feeling flawed, doubtful and overwhelmed can seem impossible. But they’re finding ways to create a meaningful life for themselves and helping others do the same.

Some students find strength in friends or family, some rely on the services offered on campus, and some dig deep to find their passions. Perhaps one of the greatest strengths of the millennial generation is how connected it is, especially to friends. Rooney says friends are often the first resource students turn to for help with worries about mental illness, and many times, those coming to the counseling center are accompanied by a close friend.

Parrie is reconnecting to campus life, to friends and to herself. She’s taking on responsibility and finds out if she was voted student body vice president on Wednesday night. She tries to carve out time each day to take a breath and focus on herself. She’s also learning how not to feel guilty for doing so.

Armstrong knows she’ll always be learning to manage her mental health, but she’s been steady lately. She’s working on it. A character in Armstrong’s novel, inspired by one of her closest friends, sees it as his mission to ask as many people, “Do you know what I like about you?” His answer is always the same: “Everything.”

Armstrong has the acronym of that question “DYKWILAY” tattooed on her arm as a reminder of what she went through, much like Parrie’s tattoo. They are permanent reminders of defeating doubt.

With help, millennials can be comfortable with imperfection. They can find out that, sometimes, it takes help to learn how to let go of what the world demands and seek happiness instead. Sometimes it’s OK to show weakness.

Sometimes, it takes a pause to move forward.

Campus Resources

There are numerous groups on campus dedicated to mental health awareness, education and solidarity.

› Wellness Resource Center: Located in the MU Student Center, the WRC plans student programs and events that deal with wellness in relation to stress, mental health, alcohol abuse and other issues. 882-4634, wellness.missouri.edu

› MU Student Health Center: With more than 25 health professionals, the Student Health Center offers resources for stress management, relationship issues, behavioral health and more. The Behavioral Health Center is located here as well.

› MU Counseling Center: The counseling center helps students with emotional, social and academic concerns through individual and group therapy, couples counseling, crisis intervention and outreach presentations. 882-6601.

› Online screening: Take a brief mental health exam.

› RSVP Center: The RSVP Center provides crisis intervention, advocacy services and holds programs and events to end rape, sexual assault and relationship violence. 882-6638.

› MU LGBTQ Resource Center: The center offers a safe place for all students and educates people about sexual and gender identities. 884-7750.

› National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Connect to a trained counselor at a crisis center in the area, 24/7. If you feel you are in a crisis, whether or not you are thinking about ending your life, the Lifeline is there for support. 1-800-273-TALK.

This article was originally published on Vox Magazine on November 19, 2015.