On the last day of 2017, YouTuber Logan Paul rang in the new year by uploading a video of himself and three friends vlogging a trip through Aokigahara, Japan’s “Suicide Forest”. Located just north of Mount Fuji, Aokigahara has long been associated in Japanese folklore with death and ghosts, but it was in the 20th century that the beautiful volcanic forest became a popular destination for suicides. Paul’s video would have been thoroughly tasteless even if all he had recorded were trees and ferns. But Paul and his friends encountered a corpse, an apparent result of one of Aokigahara’s many suicides. Paul greeted the discovery with a horrific nonchalance, laughing at his friend’s discomfort. Assuming his discovery of the corpse was real and not a macabre stunt for views, it may have seemed to Paul that he had struck clickbait gold. When has Markiplier ever stumbled onto a fresh corpse?

Paul’s video caught fire in the worst way. He was roundly condemned by fellow YouTubers such as JackSepticEye, while mainstream media pounced onto the video as one last source of outrage at the end of the outrageous year that was 2017 (the video has since been removed, and Paul has released a tepid apology on Twitter). It’s tempting to view the whole incident as a victory of good taste over bad, but it’s too early to close the casket on Logan Paul. YouTubers have shown tremendous resiliency over the years: in March of 2017, popular video game personality and former Game Grump Jon “Jontron” Jafari came under fire for comments widely perceived as white supremacist in nature, while YouTube perenniel PewDiePie has weathered a number of scandals over his career, from outrage over his continued use of the word “rape” as a punchline to an incident where he paid two Indian men to hold up a sign reading “Death to Jews” in February. But while neither Jontron nor PewDiePie are the level of superstar they once were before these scandals, they’ve hardly disappeared. Much of their respective fanbases have stuck with them and even defended them through their scandals. It seems that YouTube fame, however hard it is to achieve, is hard to lose as well.

Aokigahara (Credit: Jordy Meow)

But for all the anger Logan Paul’s video of the Suicide Forest provoked, he was only the latest in a series of Westerners interacting with Aokigahara for the sake of the camera. There seems to be a growing fascination with Aokigahara in the West: the 2010’s have already seen seven films made about the Suicide Forest, ranging from independent productions like 2010’s Forest of the Living Dead to big budget releases such as Gus Van Sant’s $25 million dollar The Sea of Trees in 2015. The most notable of these films, Natalie Dormer’s star vehicle The Forest, was released in January of 2016 to critical enmity but box office success. Not only has the Western world seemingly become obsessed with Aokigahara, that obsession seems to be growing more and more popular and more and more profitable.

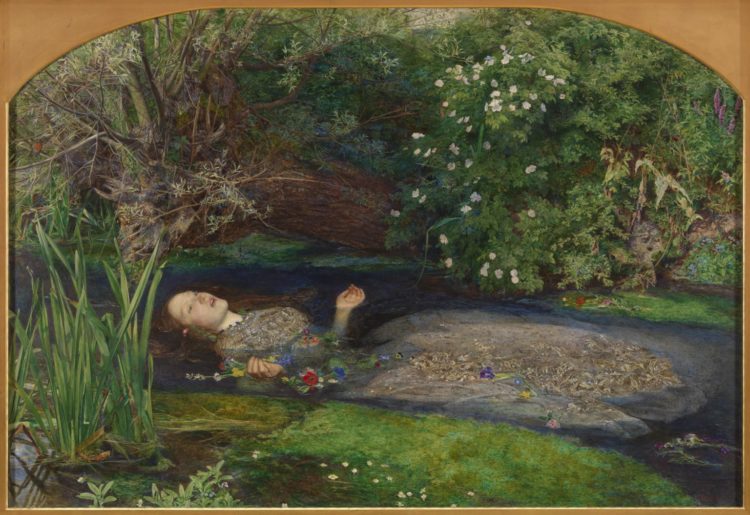

The appeal of Aokigahara as a setting is immediately apparent. A beautiful, verdant forest growing from soil made of cooled-off lava from one of the world’s most famous volcanoes is already an attraction suitable for the imagination to run wild, but the history of suicides lends it a perfect Gothic horror appeal. The idea that suicide leaves an imprint on the land, that the power of traumatic events can be felt long after their end, doesn’t just appeal to humanity’s morbid attraction to the grotesque; it soothes a kind of romantic existentialism, reassuring us that some part of us will linger on even after death in the lowliest of circumstances. This dual appeal of suicide sites has informed some of the most powerful and enduring settings in the Gothic tradition, from Castle Elsinore in Hamlet to Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, and those locales could only boast a handful of deaths each — Aokigahara averages between fifty to a hundred each year.

John Everett Millais

But there seems to be something deeper that draws Western eyes to Aokigahara in particular. The Golden Gate Bridge, another of the world’s most popular suicide spots, has drawn comparatively little pop-cultural attention, despite offering its own irony as a symbol of successful American expansionism. Americans seem relatively uninterested in our own suicide problems, so why are Japan’s increasingly the subject of our morbid fantasies? To even ask this question, we have to understand Aokigahara’s international infamy not as a recent phenomenon, but as part of a pattern of Western obsession with Japan and suicide more than a century old.

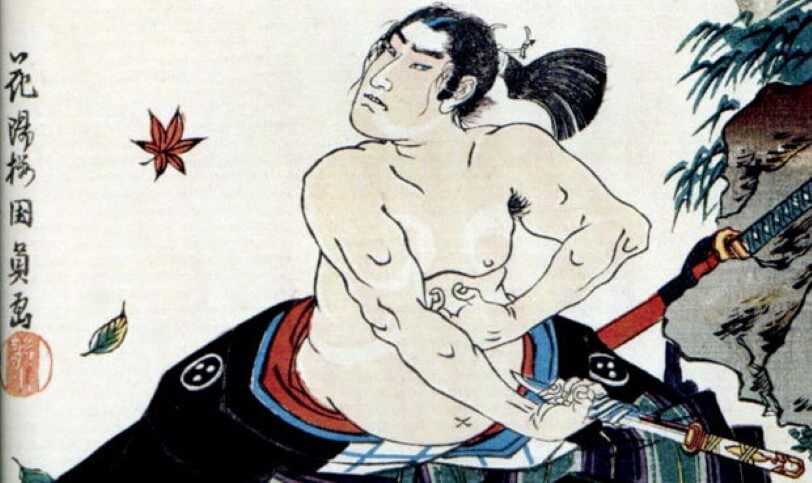

Just a few short decades after Commodore Perry forced the opening of Japan to international trade in 1853, Japanese Orientalism began in earnest in the West. The late 19th and early 20th century saw the publishing of a plethora of works set in or about Japan. Two of the most popular and influential were Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Both feature suicide as an important plot point, albeit in wildly different tones: Mikado’s first act closes with Nanki-Poo’s attempted suicide being postponed for a month so he can be married, while Madama Butterfly closes with its protagonist committing hara-kiri after discovering that her American husband has taken on an American wife instead of returning to her as promised (the latter is especially noteworthy as an early and popular evidence of Western fascination with the particularly gruesome method of suicide-by-disembowelment known as seppuku, first witnessed by French sailors in the Sakai Incident of 1868). The prevalence of suicide in Western works about Japan so soon after the opening of Japan’s ports reveals just how quick the West was to romanticize Japan’s tradition of ritual suicide.

Kunikazu Utagawa

The turbulent, complex and often antagonistic relationship between the United States and Japan across the 20th century did little to make Western depictions of Japanese suicide subside, particularly in American media. Wartime cartoons such as the Popeye adventure You’re A Sap, Mr. Jap helped make ritual suicide an intrinsic part of Japanese identity to an American audience eager to make sense of the enemy they were fighting. Japan’s desperate use of kamikaze fighters towards the end of the war further married Japanese identity and suicide to American minds, and this was naturally reflected in fiction: the shooting of a kamikaze pilot by George Bailey’s brother is a key plot point in It’s A Wonderful Life, which many American families (including my own!) watch together every year. American fears of Japan’s economic power in the 70s to mid-90s saw a new twist on Japanese suicide, as works like Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun used seppuku as a means to tie modern Japanese business executives to the violent samurai class of the feudal era.

Over the course of a century Western depictions of Japan’s ritual suicide grew more and more prominent until, by the late 20th century, suicide in general and seppuku in particular had become one of a handful of primary indicators of “Japanese-ness” in Western and especially American culture. As obvious as this trend is, however, its reasons for existence are much more unclear. I don’t propose to have one overarching explanation for the prominence of suicide in the Western portrayal of Japan; it seems to have served many variant purposes depending on the status of Western-Japanese relations at any given time, ranging from a signifier of a romantic and exotic land in the hey day of Japonism to evidence that the Japanese were an evil and barbaric people at the height of anti-Japanese sentiment in World War 2.

You’re A Sap Mr Jap

What is clear, however, is that the West’s artistic fascination with Japanese suicide has never truly been about Japan, but rather about identifying ourselves in comparison to it. Going back to Cio-Cio-san in Madama Butterfly, whose suicidal despondence over her abandonment by a white man tickles the ivories of white male power fantasy, portrayals of Japanese suicide in the West have almost always depicted them from the perspective of their effects on white people. Whatever humanitarian concern projects like The Forest have shown for Japan’s suicide epidemic are always peripheral to the greater cause of examining the effects of the exotic Orient on whiteness.

That’s why Logan Paul’s non-reaction to the dead body in Aokigahara doesn’t surprise me. It’s only the latest example of an American using Japanese suicide as a means to prove something about themselves. Maybe the backlash against Paul isn’t because he was disrespectful, or disgusting, or desperate. Maybe it’s just because he was artless.

WATCH VIDEO FROM LOGAN: SO SORRY.